My Paintings Start with Questions

A Conversation Between Loriel Beltrán and Joseph R. Wolin

MOAD Unbound, Issue Number 2, Spring 2024

My Paintings Start with Questions

A Conversation Between Loriel Beltrán and Joseph R. Wolin

Joseph R. Wolin: Can you describe your studio process, step by step, for us?

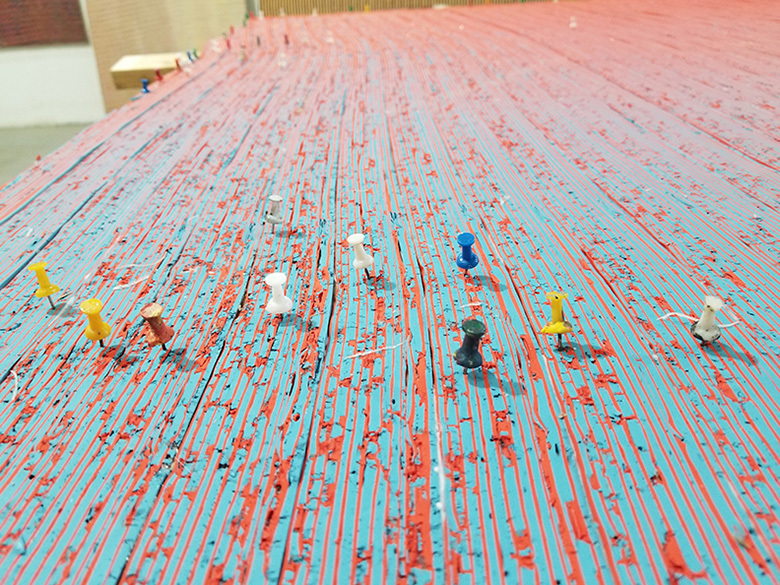

Loriel Beltrán: The process to make these paintings is slow and labor intensive. I make the paintings in groups, and I start with sketches of color ideas and a rough format of the works I want to make. Then I make custom rectangular molds in which I start pouring the paint, layer by layer. I pour a color and let it dry for about two to three days; then I can pour the next color. I repeat this process for a few months until the mold is full. I remove the block of paint from the mold and set it up in a custom-made cutting machine. The machine has a guide for a guillotine blade that gets pulled by a hoist while the paint is held by a pressing system made of car jacks welded onto a steel plate. The paint comes out as strips, and those get arranged on custom tables that have built-in storage racks. After all the blocks of paint have been cut, I start pulling out sheets with strips to decide a final format and composition. Then I make wood panels sized to the specific formats, transfer the material onto the panel, and glue the strips down to finish each painting. I hope this doesn't sound too dry. It's hard to describe a technical process in an exciting way.

JRW: Where did this process come from? How did you develop it and why did you decide to make paintings this way? Was it necessary to "reinvent" the process of painting in order to "reinvent" painting? Are you interested in the metaphorical associations that the process has?

LB: The process developed slowly and has changed over time. It started in my last year of high school, with a painting palette that I used for mixing my paints. I didn’t like to scrape the paint off or clean the palette after every use, so the paint began to accumulate. After a few years of painting, I realized I was much more interested in the accumulation of paint on the palette than in any of the more traditional paintings I was making at the time. I really liked the spontaneous growth and especially the idea that every painting I had made till that point was somehow present in that object. One day I decided to cut the palette in half to reveal this history, and, from then on, I started experimenting with slowly building up slabs of paint to be cut.

I moved to the U.S. when I was fifteen and I felt really disconnected from the culture here, so I think making these accumulations was like building a literal ground on which to start making my own work. Painting is a medium that is so old and has such a rich history, and I thought that making paintings this way, rather than reinventing painting, was more like connecting painting with this vast history of cultural accumulation and thinking of painting as objects rather than images. These ideas of painting as accumulation, painting as object, still drive my work.

JRW: Was your childhood in Venezuela influential on your development as an artist or on your current practice? Several writers have compared the optical effects of your painting—the retinal stimulation it provokes—to similar effects in the work of the great Venezuelan abstract modernists, who are often grouped together, however imprecisely, under the genre of Op Art: Alejandro Otero, Jesús Rafael Soto, and Carlos Cruz-Diez. Is this a lineage to which you feel a connection?

LB: Yes, in Venezuela you see this work everywhere, from the side of the highway to metro stations. Even the airport has a major—and amazing—site-specific work by Cruz Diez. So, it definitely has had an impact on me. I am indebted to the optical mixing of colors of Cruz Diez, the vibrant line of Soto, and the rhythm of Otero, to name a few things. But just as I am influenced by them, I am also critical of many of the assumptions they based their work upon, like the utopian promises of modernity, celebrating industry over nature, and their desire to “break” from history.

Another Venezuelan artist who has greatly influenced my work is Gego. Her work process, with systems that “grow,” her use of line as object, the way she found the architectural in the organic, I think are very much part of the lineage of what I am doing. She has sometimes been grouped with the Neo-Concrete artists of Brazil, and I definitely have more affinity for the theories that spurred that movement than those of Op Art, even though I don’t consider myself a Neo-Concrete artist; I just think it is a better place to start the conversation about lineage. Op Art sounds like the gimmick of an optical illusion and I definitely reject that. The Neo-Concrete artists were interested in the “real,” in creating autonomous objects that you had to encounter, for which you had to be present; the work creates itself anew every time you encounter it. This is much more interesting to me.

JRW: Op Art got a bad name almost as soon as it appeared because it was so easily co-opted as kitsch. There is the famous story about The Responsive Eye, The Museum of Modern Art’s seminal Op Art show in 1965, when attendees at the opening reportedly arrived in dresses printed with Bridget Riley patterns. Your criticism of the “big three” Venezuelan modernists, on the other hand, might be extended to most of modernism itself and its ideal of utopian progressivism, the notion that science and technology (and art) would lead us to what we might now call an equitable and sustainable future. Of course, we have discovered the hard way that that is not necessarily the case.

LB: Exactly! I think modernists underestimated the complexity of nature. They thought the factory and the lab could replace it, and they were certainly wrong.

JRW: But I wonder about other influences on your work, perhaps some closer to our own time. In particular, I am curious to know if you think about Jack Whitten, the American abstract painter? In a certain way, your recent works seem to recapitulate two phases of his career, his optically buzzy canvases of the 1970s, which relied upon closely spaced black and white lines for their effect—not so unlike Soto—and his later mosaic-like “painting-as-collage” works of the 2010s, in which he affixed solid squares of pigment to the support.

LB: I am so glad you brought up Whitten. I have only been aware of his work for a few years and the more I learn about him the more I feel connected to his work. You can definitely draw parallels between the work you mention and my work, but I think the affinity runs deeper. The fact that he was a builder and a taker of odd jobs informed the processes he could bring into painting, because he had that knowledge and those tools. For example, for his “slab” series of the 1970s, he built a giant platform and a giant squeegee to produce paintings in a “single stroke” and in a “single plane. These predate Gerhard Richter’s squeegee paintings by about a decade, and they come from such a different place.

I have also had to take many jobs in order to be able to produce my work. When I first came to this country, I was legal, but I did not have a work visa for many years, and I took many odd jobs. Even after I was able to legally work, I kept taking jobs independently, mostly building and installing exhibitions, because I am interested in the built environment, labor, and so on. That way, I was able to gather the knowledge and the tools to produce whatever I need to make at the studio. I do not think I could produce these extremely complex paintings if I did not have this background—unless I would have won the lotto or something.

I also think a lot about Whitten’s “DNA” series, a group of small square paintings in which he painted abstract forms, and once dry, he covered the surface completely with paint, and then raked the surface to create a grid that partially revealed the forms he previously painted. I love the way the art historian Richard Schiff describes these works as a merger of image and raster, the raster being like a projection screen, on which any possibility can emerge, and the image as the message transmitted by this “screen.” I think a lot about code and the possibilities of the painting’s surface, and how the imperfections in my paintings activate the potential of the system I set up through codes of color. I also think of DNA and the way this complex code allows for mutations and change.

The way Whitten thinks of his paintings as subjects is also interesting to me. I stay away from series, even though I work on paintings in groups. Each painting needs to be specific, like a subject. I could go on and on about Whitten.

JRW: In your own paintings, how accidental is the “accident”? How much control do you allow yourself to have over the way your system enables paint to layer, to build up and crust over, to stratify and ossify? And might you say something about your color? How do you choose your palettes? What sorts of meaning should we look for in your color?

LB: The accidents are sometimes controlled, sometimes completely unexpected. I still do not understand exactly what makes a layer crack when it dries; they behave differently all the time. I purposefully do not level my tables so gravity can become an element. And the process is pretty much blind, since I cannot see what happens until the end, when I cut the block and the work is ready to be glued.

But there are other “accidents,” or, as I prefer to call them, interruptions, that are more intentional. I might pour a similar sequence of colors on a different surface, peel it, and then add it inside the mold. Sometimes I dip pieces of dry paint in wet paint and hang them to dry and repeat the process multiple times until I finally throw it into a painting in progress. Or I cut specific shapes or symbols and insert them at some point in the pour. I have been doing this more as I understand the color palettes better, and I can be more intentional as far as what I want to explore with each piece. For example, I have been working on a few paintings using primary colors. You can create any color by mixing primaries (plus white), so I am interested in this idea of primary colors as building blocks for experiencing color in a phenomenological, or primary way. I think of how this is different than language and other “mediated” experiences, so I have been adding signs and symbols into these primary palettes to put these two ideas in tension.

Other palettes come from ideas in traditional painting, like mixing pure complementary colors to create realistic color. For these, I have put two complementaries against each other (blue-orange, red-green, purple-yellow, and everything in between). These paintings usually have two readings: one from far, where the colors optically mix into a neutral field, and from close, where you can see the pure colors reacting against each other. And, many times, I choose colors that are not only opposite to each other on the color spectrum, but also that are of the same value, to create an effect that is called simultaneous contrast. This makes the two opposing colors seem like they emit light, almost as if they were creating a chemical reaction.

On the subject of light—I have worked on different variations of color spectrums that also seem to emit light. These are the ones that I think work like the screens I mentioned before, teeming with potential. I think there is something really interesting about paintings that seem to emit their own light. Light has always been such a central concern of painting. I have also worked on the opposite of this, by trying to make very dark paintings that are still chromatic. These absorb light, but, as you engage with them, they have areas of contrast where they seem to emit light as well, creating a pulsating effect.

Usually my paintings start with questions, and I am not interested in creating a specific meaning. Using only line and color, I want to be able to distill important ideas of painting into the picture plane, and make paintings that are transparent in their process, yet very complex in their reception by the viewer.

JRW: The optical effects of your paintings depend on the presence of the viewer and on the particularities of size, scale, distance, lighting, etc. They do not work as reproductions and they range from the allover retinal dazzle common to most of them, resulting from the tonal difference of closely spaced bands, to the even more viscerally felt warping of space that occurs in some of the larger panels. OBSDV (2020–21), for instance, gives the illusion of curving out towards the viewer at the top and bottom, while the broader stripes of FSLTD (2018–20), make space appear to bulge in and out in an unpredictable, vertiginous way. For the viewer, these sorts of pictorial happenings feel both exhilarating and slightly unsettling, like a roller coaster. How much of this do you seek intentionally and how much are you able to control it? What kind of meaning do you ascribe to these spatial anomalies? Does their presence hint at another lineage, beyond the formal, to which your work belongs, one that might include not only abstract artists, but also representational painters who similarly twist and fold space to dizzying effect, such as Picasso or even David Hockney?

LB: These definitely do not work as reproductions; they need to be experienced. But I am not looking for any specific illusion, even if they sometimes happen. The warping is a result of the block of paint not being exactly equal throughout the piece, and when placed together, those differences accumulate and create an undulation. For example, in the two works that you mention, I first glued the two central strips as straight as possible, and then I kept gluing the rest of the strips outwards. The difference in size of each strip accumulated, and by the edges of the work, there was a lot of undulation. Other works are aligned on the top and have the error accumulated on the bottom, and it gives a feeling of weight. I like this idea of the accumulation of error, letting the work fall into entropy. The decision of where to have the error accumulate is very much intentional; the difference in the size of the material, not so much.

As far as lineage, I think these are more connected to artists working with systems and chance than with Picasso or Hockney. In the modernist divide between Duchamp and Picasso, I think these are much more Duchamp, and they are probably closer to artists like Sol Lewitt, Robet Morris, Lynda Benglis, or Gego. The funny thing is that these illusions you talk about are completely different for everyone. In OBSDV, I see atmospheric space and depth, and, in FSLTD, I see a potential energy that builds up, and, at some point, you need to turn away from looking at it. But, in general, I like that these paintings seem to generate their own images/realities, depending on how you see them, while showing you the scaffolding of line and color that makes them possible.

JRW: This is a moment when painting is very much again at the forefront of artistic discourse, but it is figurative painting that seems to be getting all of the attention, especially figurative painting by artists who are members of previously underrepresented groups. Abstraction as a mode for critical painting today has not received much attention. This past fall, in fact, no less an eminence than Hockney declared that abstraction in art had “run its course.” What is the continuing appeal of abstraction for you? What can it do for us as viewers? What can it do for painting and for art?

LB: I am really glad abstract painting is not what is hot and of the moment right now! I am sure Hockney heard that figurative painting had run its course so many times in his life that he must feel vindicated. But I think this recent interest in figurative painting is just another run of the cycle; this trend will end up like “zombie formalism” did not too long ago. All fads run their course. The most innovative artists from the moment will endure, and the ones that are just following the pack will be forgotten.

I like to think in longer time frames, and my interest is not necessarily in abstraction, but in painting. Since the invention of photography, painting has had to contend with other, easier ways of creating images, which generated so many new ways of painting, as well as many declared “deaths” of painting. I want to make paintings that are so complex that they resist becoming images; I like to think of them as anti-images. I want the viewer to be present and experience the work as something so complex and active that it cannot be grasped all at once. Time is really important, not only in the making, but in the viewing. Painting needs to assert its place in the digital age and really challenge this image-centric culture of connectivity, speed, and turnover. I want my paintings to be slow and stubborn, yet timeless.

JRW: So, where does your painting go from here? Where do you want to take it? Where do you want it to take us?

LB: I would like my paintings to open new ways of seeing. I think it is important to be critical of images. So many paintings are made that fully accept that they will be disseminated as images that I wonder why they were painted in the first place. I think we need something like a Pictures Generation of our own time to think critically about this relentless image production and flow. But I think painting should exist somewhere else than as a reproduction, and it should not be easy to paint. There is a physical and historical aspect of painting, the performance and confrontation, that somehow should still be palpable. We encounter painting in person to experience it in the resolution of the real. Not to be anti-digital—I am sure that one day this other reality we are building might be as complex as “the real,” but the fact that the digital has taken so much of our imagination and attention does not mean that it is a better way of seeing.

This conversation took place by email between August 16, 2021, and March 26, 2022.