Pleated Time: On Loriel Beltrán’s Layered Paintings

Juan Ledezma

MOAD Unbound, Issue Number 2, Spring 2024

Pleated Time: On Loriel Beltrán’s Layered Paintings

Juan Ledezma

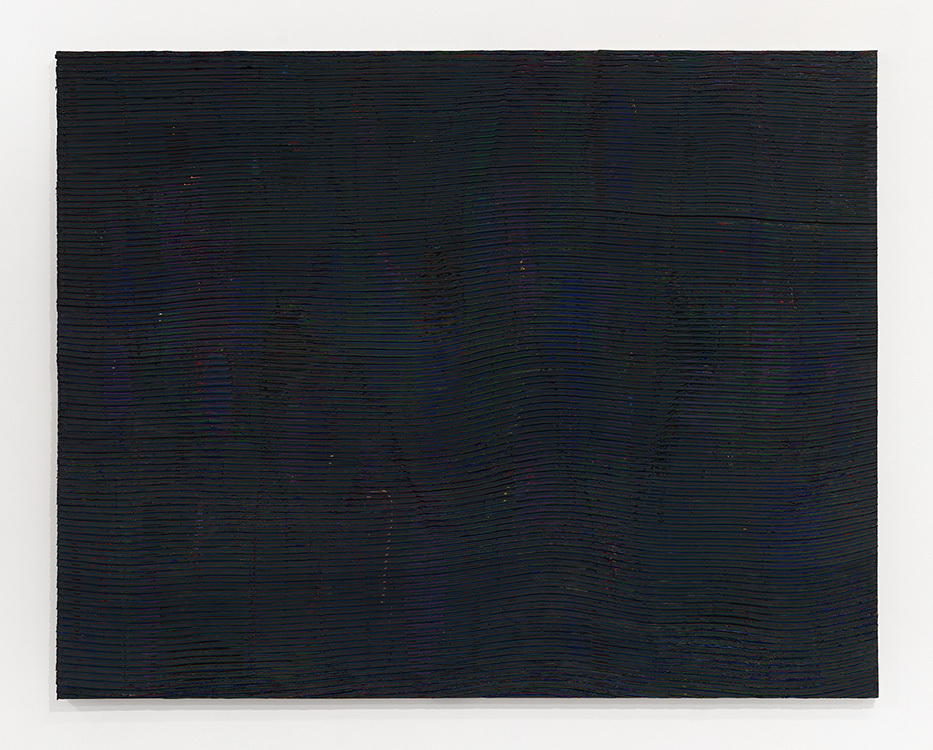

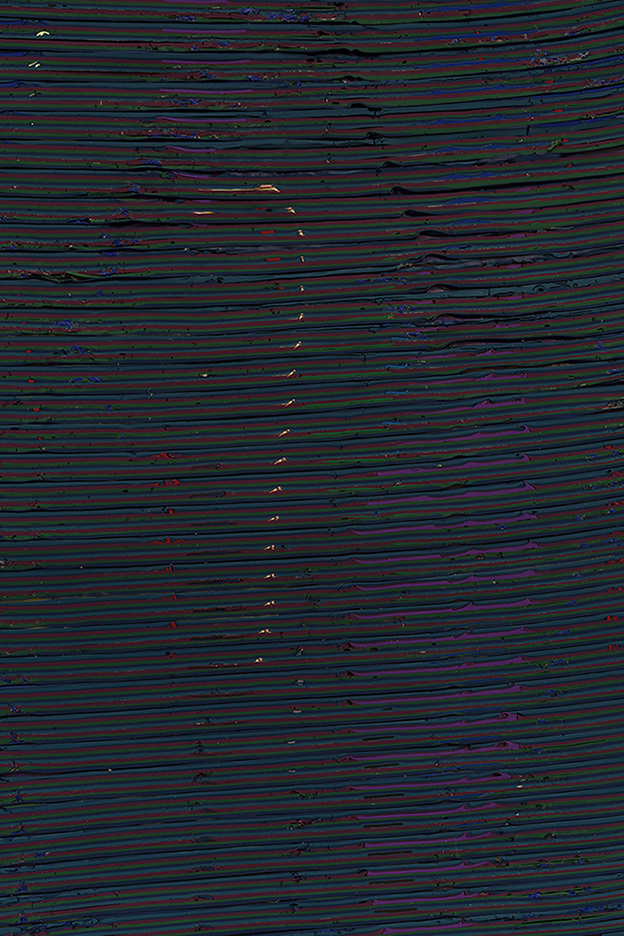

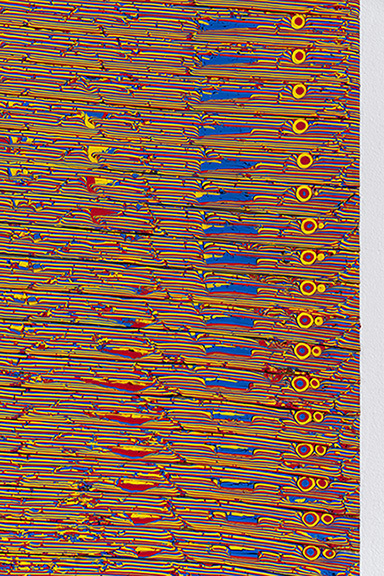

Loriel Beltrán constructs color through a process of assemblage. His works shape up as coats of latex paint, poured within troughlike wooden crates, annealed to the consistency of supple blocks; he transversally slivers the blocks into stripes and glues the stripes on a board in an all-over pattern. Beltrán works with preparatory drawings, studies informed by color theory, which anticipate the moment when optical sensation will take over from production. In tandem with the incidence of light and the eye’s scanning motions, the assembled hues—white interspersed in sets of either primary, secondary, or tertiary colors—blend into a tight optical mesh and the lump-filled paintings contract into wavy monochrome impressions. Yet, as viewers retinally perceive color within its own evanescent field, they haptically sense it around the painting’s ridges and grooves, and thus the immediacy of optical blending yields time and again to the work’s facticity—the already hardened settling of paint’s inorganic matter, the bendings of the latex that register as striated drippings, the indexical traces of color’s assembly. Beltrán’s “layered paintings” sustain an immediate tension between sensation and production, with the latter foregrounded by the fact that the work’s stripes layer or abut on each other in stacked arrangements that recall the piece-by-piece configuration of assembled objects.

If viewers, looking against the grain of optical illusion, reconstructed the works’ production process from such material cues, they would have to reckon with the additional fact that the artist’s post-easelist practice proceeds as both invention and inventory. Beltrán’s materiological research also busies him with the cataloguing of the crates by way of labels such as “Primaries/Secondaries. Low Value Vertical Wavy” (descriptors of a work’s planned makeup) or “1. Infatuation. 2. Laser. 3. Spa Blue. 4. Exotic Blossom” (identifiers of the layered paints). The inventory of color further engages him in storing the cut stripes on a cabinet’s slidable trays, instruments for the retrieval of information on the works in progress. With the serial logic of the catalogue thus carrying over into the mechanics of storage—a mechanics to be recapitulated in the sequential assemblage of the paintings themselves—the time of production marks the step-by-step compilation of knowledge about chromatic facts. It casts itself as the tabulated and ever accretive time of the archive.

As anticipated by Beltrán’s preparatory drawings, the time of the product, which is to say the time of form, abbreviates to the singular moment of aesthetic experience. It condenses into the interface between artwork and viewer an encounter made up of those multiple yet unrepeatable instants when the painting’s striated spread yields to sensate reception: the wobbly surfacing of optical effects, the unsteady coherence of a body of color atop and against the sequence of sliced latex. Since such a sequence also registers as a serial, methodical compilation of encrusted hues, and thus patterns itself on the accretive research that marks the artist’s production, form’s emergence also contracts the time of archival classification into that of aesthetic intuition. It collapses the production of knowledge in the immediate, non-cognitive condition of pure sensation. Yet, as the moment of form must be won over a material substrate recalcitrant to its optical dissolution, the temporal contraction it involves also translates as a tension-filled dilation. Taking a cue from the artist’s account of “contradictions [as] the bookends of an idea,”[1] we might then choose to address his works neither in regard to intuited form, nor in attention to matter, but in terms of the notional field they construct for painting. To do so would imply pleating together the physical time embedded in the paint’s deep striations, the structuring time foregrounded by the object-like quality of the works, and the time of the archive as a social practice. It would imply stepping away from the presentness of optical sensations and perceiving painting within a disjointed temporal frame.

Framed Matter

These are no longer times for Michael Fried’s modernist “opticality,” or the alignment of the work’s materiality into a strictly visual field, the aesthetic coherence of which would be “wholly manifest . . . [in] a kind of instantaneousness.”[2]

The current moment rather accords with David Joselit’s “transitivity,” namely contemporary painting’s disposition to fold into itself the extra-pictorial conditions of “social networks”—“historical, topographic, and epistemological” contexts with which painting would connect through a set of “intersections.”[3]

Whereas Fried’s search for “instantaneousness” rejected time as the mark of our progressive perception of actual space—an obstacle to eyesight’s grasp of the work in “all its depth and fullness”[4]—Joselit’s encounters with “painting beside itself” turn to the distinctive temporality of “passages” between the pictorial object and the networks with which it comes to intersect. The question pertains to framing. Fried adverted against the minimalist object’s “presentment of endlessness” as it “persists in time” and thus resists being framed as an aesthetic unity.[5]

Joselit remarks on how “the body of painting is submitted to infinite dislocations,” so that its “framing conditions cannot be quarantined.”[6]

“What defines transitive painting,” Joselit further submits, “is its capacity to hold in suspension the passages internal to a canvas and those external to it.”[7] This definition applies to the junction between site and abstraction that informed one of Beltrán’s early works. Produced in 2009 at Miami’s Locust Projects, an institution engaged in sponsoring site-specific art, the work entailed removing blocks of compacted paint layers from one gallery’s walls, so as to strip bare the mark-making mechanics of nailing, cutting, and sealing involved in the installation of past exhibitions. These memory traces, the material imprint of the institution’s history, provided the ground for the display of monochromes that Beltrán assembled by gluing thin strips of the paint blocks onto wooden panels. The monochromes, therefore, were not only tied up with the specificity of a site; they also were that site reconverted, and so registered the reciprocal “transitive action” between painting and its social surrounds that Joselit detects in contemporary pictorial practices. These works, moreover, anticipated the layered paintings as regards their mode of construction and the issues that it would raise; rendering visible a “cross-section,” to use Beltrán's term,[8] of the gallery’s exhibition record, their striated matter took on temporal breadth and posited production as an archiving process.

Imbricating with their surrounding site along a physical axis, the monochromes reframed that site in temporal terms. The question of framing carries over to the layered paintings, but turns on the internal disalignment between the work’s disparate temporalities, which now include, besides the physical time of matter and the structuring time of the object, the time of form’s emergence as a perceptual phenomenon: whereas the stacked strips of the white monochromes tend to read as literal shapes, the color mixtures sustained by the layered paintings reintroduce the illusion of a nascent space, a form cohering above the work’s literal construction. The series thus reinstates the modernist paradigm of opticality, yet not to assert the immediate presentness of a wholly graspable color field. The series involves instead a mode of reception that shifts along with the work’s registers of time, and so the question becomes how to follow the disjunctive passages across such registers.

If modernist opticality is here granted a contradictory afterlife, what other paradigms might then inform these paintings? How could they account for pictorial matter’s insistence on bulging through the field of color mixtures, which is to say its resistance to such a field’s formal unity? And how could they explain matter’s own disjunction between the arrangement of the stripes, the methodical character of which speaks to the archival logic of color’s production, and the inorganic process of paint’s sedimentation, the random quality of which exceeds the classificatory scope of the archive? Among the stock of paradigms provided by the pictorial medium’s history, it is monochromatic painting that most appositely affords answers to these questions, since the monochrome both collapses the distinction between form and matter, the spread of a color field and the facticity of surface, and demands that it be reconsidered anew. And, as the question here is how to enframe the work’s temporal modalities to assess their disjunction and unity—or their disjunction-in-unity—the most pertinent reference may be Hélio Oiticica’s handling of the monochrome. For it was Oiticica’s distinct contribution to have coupled time and the monochromatic plane in a new model of vision—vision recast as duration.

Duration is Henri Bergson’s term for lived time or time experienced as moments that interleave each other, rather than quantified as distinct sections of a unilinear sequence. “A continuous or qualitative multiplicity with no resemblance to number,” duration opens itself to what linear time excludes, namely the prolongation of prior experience, via memory, into actual perceptions, such that the past is retained in the present as a virtual force capable of projecting itself toward “a new grouping, in a new order, of elements already perceived.”[9] Bergson’s oft-quoted analogy for such a state of consciousness is that of “the notes of a tune, melting, so to speak, into one another.” Oiticica provided the notion of color as “a complex thread of virtualities” to be ever newly actualized.[10] In his Nuclei (1960–63), compound assemblages of hanging planes, color “develops” as minute tonal differentiations of a monochromatic constant, a “leitmotif [that] pulsates” as it gathers and loses intensity from one plane to another. The “passage from color to color” would thus be grasped as a continuously recalibrated interconnectedness, whereas matter, or pigment’s intrinsic tonal dynamism, would be confronted as virtuality: not a fully differentiated datum, but a vast reserve of differences awaiting concretion.[11] Rather than constituting a binary in which the first term imposes its shaping rule on the second, form and matter (i.e., the interconnectedness of color planes and pigment’s flowing virtuality) would then engage each other as equally dynamic forces. They come to coexist in the Nuclei as the mutually determining components of multiple recombinations.

Beltrán’s paintings also involve the accrual of interleaving moments in the process of their perception. This is most clear in paintings from 2018 in which two distinctive color sequences extend laterally above one another. At a given viewing distance, the tiered sequences dissolve into their own pools of contracted color and the work furtively appears as the juxtaposition of two emerging monochromes. This impression’s counterintuitive character transpires at the conjunction between the tiered fields, a middle band where optical mixing comes undone: not as closely knit, and hence not perceivable as a swath of color, the stripes there register the sheer gluiness of unblended latex paint. This middle band thus marks itself off as an element that demands a specific exercise of perception. For it is the viewer’s glance that takes in the near-monochromatic spread of the upper and lower tiers; here vision slows down into a stare involved in reading what the painting is materially—a ridged body of latex, the annealing of which remains manifest in its striations. Vision embraces the lengthier pace of attention to confront the encrusted time of paint’s passage from liquid to solid, which is foregrounded by the capacity of the latex, on account of its suppleness, to picture an in-between state of suspended liquidity.[12] In marking a temporal breach, however, the middle band also modulates one moment of the work into the other. It blends up or down with each of the two tiers—its borders leak, as it were, into what they frame—and in so doing delineates an area of indistinction rather than a clear-cut edge: an intermediary moment when the unsteady form that defines the color fields comes undone in the material, just to recoil and reemerge via the viewer’s further engagement with the work.

Archived Sensations

The reciprocal shift from glancing to staring might otherwise be described as the alternation between the comprehension of the painting as an optical field and its apprehension as a segmented construction. It translates the alternation between the emergence of a cohering form and its renewed dissipation via our encounter with the materiality of the work. The central point here is that every reemergence of form would be carrying with itself the memory of its breach. They would not so much trigger the instant of aesthetic conviction as forge the recollection of a process, thereby gathering, to requote Bergson, into “a new grouping, in a new order, of elements already perceived.” This, too, confirms the heuristic value to be found in Oiticica’s durational model of the monochrome, for it is the reinitiations of form—the capacity of the work for “always making itself present, always recommencing the impulse that generated it”—that provided one key component for the Brazilian poet and Neo-Concrete theorist Ferreira Gullar’s concept of the “non-object” that so influenced Oiticica’s production of the 1960s.[13]

Yet such a concept also enfolded a perception of the artwork as quasi-corporified within the phenomenal setting of its “appearance”—in the “pure event,” that is, of its reception—after which its strictly sensorial materiality would dissipate “without leaving a trace.”[14]

And one condition of Beltrán’s layered paintings is that they provide the monochrome with a structured support, the modularity of which not only relates them to constructed objects, but also retains the traces of the archival logic involved in the artist’s pictorial labor. One then needs another set of strategies, a second reference, the heuristic value of which would now lie in its capacity to hold sensation, object, and archive together in meaningful correlation.

We could start by looking in the direction of the architectural models that Kazimir Malevich assembled in the 1920s. In contrast to the constructivist object, Malevich’s arkhitektons address no specific function. They instead posit architecture as both a pre-given framework and the diagram of untested relations—an ever-fragmented “mass in motion,” the splintering of which deranges constructive givens under the pressure of proliferative “sensations.”[15] Extrapolating from such a referent—and using it in a way that is heuristic rather than historicist—one might substitute archive for architecture. It then becomes more concretely apparent how the archive’s structure both informs Beltrán’s production as a functional expedient—the inventory and storage of color—and might itself be transformed in the constructed paintings. For, if the social practice of archiving generates knowledge and serves the purpose of memory, then the tabulated layouts of the series not only adopt the arrangement through which color is catalogued and stored in the artist’s workshop. They also reorient the archive’s cognitive and mnemonic structure toward the construction of sensation; their tabulation provides for the sequential cognitive grasp of color’s facticity, but it also supports the redistribution of color through its overlapping mixtures, its cumulative layering as moments that verge on one another and thus durationally distend between recollection and projection.

The work once more conveys itself as temporalized, only now according to a rhythm that joins a modular spatial framework, the structure of which allows for the sequential display of chromatic facts, and its temporal modulation along the layered production of color events. The latest paintings in the series set up a different, though not unrelated, perceptual situation. By inserting dry morsels of paint into the still congealing blocks of latex and thereby disrupting their stratified molding within the crates, Beltrán now “amplifies,” as he puts it, those “imperfections in the pouring” that result in the accidental tears and variations in thickness of the stripes. He creates such disruptions in sequence, at intervals that in the finished paintings will prompt the appearance of a pattern—a throb of cluttered color, the steady beat of muddled daubs across the painting’s surface. Beltrán calls this pattern a “code” and understands it in terms of the inscriptive logic of “language.” [16]

These serialized inscriptions thus come to punctuate the work by means of marked disruptions we scan in a sequence homologous to that involved in reading. Only this code resists its decoding, as there is no established system for its intelligible reception, so that its meaning fails to be relayed. Coding the material, nonetheless, broaches the question about matter’s concrete expressivity anew—the question of the terms in which matter itself might be said to attain and release significance.

The code of the new set of paintings is “a pattern that starts to emerge,” as Beltrán describes it, but the emergence of which grounds itself in the unpatterned, random exfoliations of the latex that register the disruptions in its process of annealing. The code thus casts its intervallic structure—comparable, in this respect, to what this essay has been describing as the archive—on the indeterminations of chance. Its coordinates are themselves disrupted, disjointed by matter’s unruly expressivity, and so the code involves a contradiction similar to the productive tension that informs what Gilles Deleuze calls a “diagram”: a plan of construction that proceeds by derangement, debunking as it does a “sovereign optical organization” that constrains visual sensations under its rule. [17] For the diagram introduces an order, yet one in the process of emergence—an order, the tentative coordinates of which still allow for the material to be unsettled and pushed toward other expressive possibilities, uncontrolled and unforeseen. Beltrán proceeds diagrammatically in the series as a whole, as he reclaims from opticality’s organization its emphasis on the visual to construct retinal sensations otherwise: optical and haptic, present and archived, actual and thrown into temporal relief. It is sensations that are layered, informed by a production process that itself opens onto other modes of labor and archiving. They are assembled within and in excess of painting, along an unfolding field of construction and its pleated time.

[1] Loriel Beltrán, email to the author, July 11, 2019.

[2] Michael Fried, “Art and Objecthood,” Artforum 5 (Summer 1967), 22. Reprinted in Fried, Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 167.

[3] David Joselit, “Painting Beside Itself,” October 130 (Fall 2009), 132; and “Reassembling Painting,” in Painting 2.0: Expression in the Information Age, ed. Manuela Ammer, Achim Hochdörfer, and David Joselit (Munich, London, and New York: Prestel, 2016), 173.

[4] Fried, “Art and Objecthood,” 22.

[5] Fried, “Art and Objecthood,” 22.

[6] Joselit, “Painting Beside Itself,” 134.

[7] Joselit, “Painting Beside Itself,” 129.

[8] Loriel Beltrán, email to the author, September 14, 2021.

[9] Henri Bergson, Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness (London: MacMillan, 1913), 105; Bergson, Creative Evolution (New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2005), 5. For a brief discussion on the topic, see Cliff Stagoll, “Duration (Durée),” in The Deleuze Dictionary, ed. Adrian Parr (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 78–80.

[10] Henri Bergson, Time and Free Will, 100; Hélio Oiticica, “The Transition of Color from the Painting into Space and the Meaning of Construction” [1962], in Hélio Oiticica: The Body of Color, ed. Mari Carmen Ramírez (Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2007), 222.

[11] Hélio Oiticica, “July 11, 1961,” in The Body of Color, 247.

[12] For a discussion on “glancing” from a Bergsonian point of view, see Edward S. Casey, “The Time of the Glance: Toward Becoming Otherwise,” in Becomings: Explorations in Time, Memory, and Futures, ed. Elizabeth Grosz (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1999), 79–97.

[13] Ferreira Gullar, “Manifesto Neoconcreto,” Suplemento Dominical do Jornal do Brasil (Rio de Janeiro), March 22, 1959, 4–5. Irene V. Small relates matter and memory—the title of one Bergson’s key books on duration—in her discussion of Oiticica’s Série Branca (white-on-white paintings): “this durée corresponds to the viewer’s gradual accretion of aesthetic information. Rather than being perceived instantaneously and sequentially, the multiple tonalities of white shift as the perception of any particular zone of painting is influenced and nuanced by the recollection of another.” See Irene V. Small, Hélio Oiticica: Folding the Frame (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2016), 140.

[14] Ferreira Gullar, “Teoria do Não-Objeto,” Suplemento Dominical do Jornal do Brasil (Rio de Janeiro), December 19–20, 1959, 1.

[15] Malevich geometrized “sensation” (oshchushcheniye) in “masses at rest” (the square, the circle, and the cross) and “masses in motion” (receding trapezoids). I am borrowing the term “sensation” to describe my perception of the arkhitektons.

[16] Loriel Beltrán, email to the author, May 25, 2021.

[17] Gilles Deleuze, Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation, trans. Daniel W. Smith (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 82–83. See also Darren Ambrose, “Deleuze, Philosophy, and the Materiality of Painting,” Symposium: Canadian Journal of Continental Philosophy 10.1 (Summer 2006), 191–211. On the diagram and abstraction, see John Rajchman, Constructions (Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London: The MIT Press, 1998), 55–76.